There are many layers in what we can describe as politically charged work. Certainly, when it comes to the performing arts, the way one presents the body on stage is one of them. The body can be approached as a historical archive, as a statement of freedom and vulnerability, as a powerful means to convey a message, or just as a body on stage, as natural as it sounds.

Even before seeing all the proposed works of PT.23, there was something I could sense in most of them: a debate about contemporary perceptions and the inquietudes of its creators. If PT.23 presented works that “question, state, dance, think and make our times,” as artistic director Pedro Barreiro wrote in the welcome note, then the artistic fabric of these Portuguese and Portugal-based artists may be exploring ways of deconstructing thought and expanding the edges of what is considered – as this year’s jury wrote, by no coincidence – “a performing action”.

In their introductory note, the jury asked us to join their “debate, to sit and to ask all times why art, why performativity, why courage, why doing this together.” The invitation was made and I accepted it. Recognising that there are more questions to ask than answers to assure us, I selected 10 out of the 18 programmed works and spoke with the artists to reflect upon the different weights given to the performing body on stage.

1. The body as memoir

Bernardo Chatillon, Reindeer Age #1

Everything for me is political, So, everything I’m going to do is political. In Reindeer Age #1 I invite the audience to celebrate what enchants us. My political point of view is this ever-ongoing discussion about what enchants today. Enchant – for me, or in what I say here in continuation with my other works – it’s memory. Memory is a big enchantment, you really believe in what happens or what we think that happens. And celebrating this memory is opening portals to go back and to rebuild. For example, I have a huge, beautiful relationship with my father, and I believe that it comes through my pieces, you know, because I own the narratives that I was trapped in. How do I do that? I bring, again, these memories. I communicate with them in real time and I own them. So, for example, those road trips that were really crazy – because my father and my mother were always arguing with each other, making stress and all these tensions – they stay in my body. So the moment I bring them here, I deal with them directly and I speak and I enchant them.

I make a character out of foam, which is something that my father used to use, and I use the audience to watch because all that, all this, is inside of me. I’m already celebrating it because I’m inviting people to see what was inside of me. And maybe there is this inside of you, too. So let’s celebrate it, let’s give space to this. The moment you give space to something that is peripheral, inside or trapped, you know, you are calling attention to it.

2. The body as individual affirmation

Daniel Matos, VÄRA

I think that everything we do is political, but I’m really searching more for this affective politics. We are always afraid of being alone or learning how to deal with ourselves and to relate to others within a community – this idea of being alone but together, and alone together. I really feel that this relationship between community and individual is present in VÄRA. How do I allow myself to question things that I normally just put aside because it is not allowed or is not polite or is not something I should think about because I am part of a community and I should just follow the rules? I feel that a community is built when you really question things and question your position as an individual with your own opinions, your own fears and your own visions.

3. The body as home of subjectivities

Gaya de Medeiros, BAqUE

We can counter the stereotypical discourse about the trans body by humanising it. And what is humanising? I think it’s showing subjectivities. Someone said to me when they saw my other work, Atlas da Boca: “Wow, everyone who watches this show must end up in love with you and Ary.” And I replied, “Maybe, but it’s not because we’re here like this, with beautiful bodies… It’s because this show gives you time to realise that the body carries affections, loves, feelings, desires….”

Sometimes we don’t have much time to subjectify people and they become just stereotypes. Stereotypes are the most external thing we can have, the most superficial, and in my shows I think I try to subjectify even the most futile things because, whether we like it or not, our subjectivities are not always the most interesting things in the world, right? We are not thinking all the time about politics, history, revolution… We’re oscillating between “I’m going to buy a yellow dress” or “my dog died”. So I think that by doing this, those in the audience can have links with us but expand beyond just “oh, what an intelligent person, what a politicised person, what a person who suffered”.

4. The body as war

Gio Lourenço, BOCA FALA TROPA

Kuduro, in its origin, is a political weapon, no doubt. I don’t want to impose that meaning, but it is a very clear political weapon, which encompasses several issues: war, hunger, peace and happiness. And that’s one of the things I also put into my show. Kuduro has always been approached in the sense of a dance that has a lot of power and a lot of impact and people are amazed, but its history is not often addressed. Kuduro was born in the war. The people who danced in Angola were mutilated dancers. But at the same time, I bring kuduro to connect with my country, Angola, that for me was an imaginary Angola. I no longer remember things from my country, because I came to Portugal as a child. So in this show, I usually say that I am not alone, there are many who are with me.

5. The body as endangered place

Keyla Brasil, Meu Profano Corpo Santo

In Meu Profano Corpo Santo we are talking about ritual, art and life. In this piece we talk about the body, a body that can be sacred and can be profane. My ancestors believe that this is a sacred body and a holy body, from our cults to the elements of nature. For the coloniser, this is profane, and so we were killed. For the European coloniser, when he places the sacred – which is this Catholic rite, this rite of candles, this rite of supper, this Christian rite – for us this is profane. When I take these elements, sacred to the coloniser, for me I’m laughing. For me it’s liberating, but there are many people who get up and leave in the middle of the performance.

Gender is a social and oppressive construct. Today I can be killed because of it. I come from the country that has killed the most travestis* in the world for 14 years. In Brazil, the average life expectancy of a travesti is 33 years. Yet I am alive. This means I should have been killed more than three years ago. In Meu Profano Corpo Santo, I am talking about something that can cost my life. So, I have to talk about my struggle, I have to use art as a way to amplify what I see and cannot understand.

*In Brazilian Portuguese, a travesti is a trans woman, within a specific social context related to exploited, objectified and marginalised bodies.

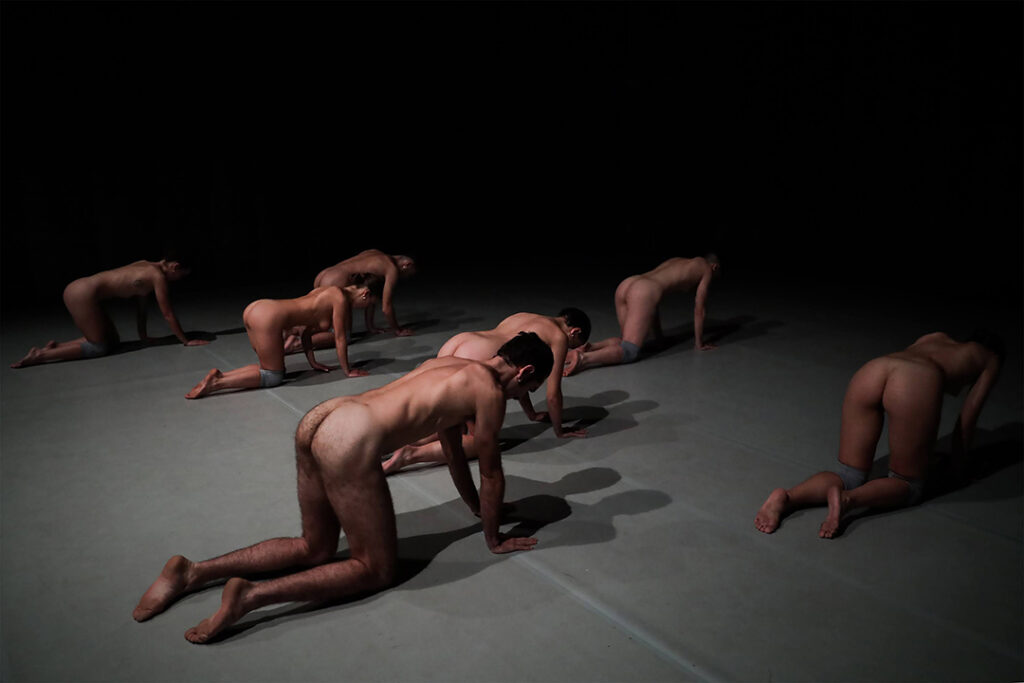

6. The body as question mark

Marco da Silva Ferreira, Carcass

Theatre is an elite space. Usually when things come to the theatre, the elite validates it. But it was already existing outside theatre, so the theatre is a bit behind something that is already happening. Sometimes theatre imposes change also. In minority communities and dance art expression, I feel like theatre is slightly behind, but at some point I don’t feel the total responsibility of theatre to recreate those outside spaces.

If a dance appears in a context, in a place, in a club, why would we illustrate it on stage, why do we have to go for the figurative? I didn’t want to put folklore figuratively on a contemporary stage. For me, the place is a more philosophical one. What questions or thoughts are we activating? What body philosophy are we working on? Based on that, I start trying to understand how I can read and also problematise these dance genres, without being afraid to touch on them in a way that is not a simple recreation or figuration on stage. I am not interested in that. I’m always looking for the edges, the limits are what interest me – of languages, of the dance styles. Through my dance experience, I have developed abilities of melting styles very easily in my body, so I can test this and then try to share this journey with other dancers, and they do the same exercise by themselves and they return them to me. For me, the stage is also this place. To question things, to try to understand edges, limits, the countermoulds of things.

7. The body as witness to ancestry

Piny, .G RITO

I think the body carries a lot of non-physical and physical memories of things that you didn’t experience yourself. It’s not that I started doing certain types of movement because of that memory, but dance for me came in a very intuitive way. Sometimes you wonder: what do you feel when you hear a song? When you put that movement in your body, you don’t find it strange, and naturally there are things that come out very easily. When you make those movements, you feel that they are yours. So, I believe that somehow this means that there is an ancestry. Sometimes people think there is a time frame, but we don’t know if it’s 100 or 500 years. We’re talking about movement, but it can be about a food you taste or a place you visit. Sometimes you feel that place is like home to you – or, on the contrary, that it suffocates you, and you think “I never had a trauma related to this place”, so you question why you are feeling this way. My body also brings that on stage.

8. The body as strength and vulnerability

Rogério Nuno Costa, Missed-en-Abîme

There is an autobiographical layer of the process of creating Missed-en-Abîme that took me to this idea of looking at myself as a person, as a citizen, as an artist, but also at all the different layers that construct my identity. That includes my sexuality. That includes the way that I identify in terms of gender, even in terms of the things that I believe in about the world, about people around me. I think that being a queer person is almost interchangeable with the idea of being invisible and fighting for a place of visibility that is constantly stolen from you in many different spheres of society. I think that that was another layer on top of the many others that kind of haunted me at some point in this process, something that I started feeling in my skin in an almost tragic way.

So this piece is an act of both vulnerability and resistance. It’s like fighting back with the things that you have. Like: okay, if I’m invisible, let’s try to do something with this invisibility. Maybe there’s some strength in being invisible and in being vulnerable. Maybe there’s some strength in the fact that I was severely bullied when I was a child and a teenager. Like, instead of just pretending that it didn’t happen, which is what we do to protect ourselves otherwise. We have many examples, many sad examples of people who cannot find a way of overcoming that. And they just want to put an end to their lives, for instance. So there’s always a point in our life that you just pretend it didn’t happen; but it did happen and it’s still within ourselves.

In recent years I have been also thinking about how being an artist also somehow makes visible those same structures of, you know, all the bad things about gatekeeping. How you are selected to be in this or that place, and for what reasons. And I think that the process is exactly the same. It’s kind of scary to see nowadays that those bullies from the nineties and eighties are coming to places of power in many different spheres of society and politics. It’s kind of scary because we all thought and believed that they were gone or that they were irrelevant, but they are not. I think that idea has sort of haunted this whole performance, this whole process. It became like a very concrete thing that I had to deal with.

The text also is very critical. It has many poetic moments and very vulnerable moments. But it’s also like touching wounds, my own wounds as well. Even though there’s one specific moment in the middle of the performance where I point at the audience, I’m not blaming them, but rather inviting them in. Like: “we are all part of this, so we are all to blame, but we can solve this together.”

9. The body as party riot

Tita Maravilha & Cigarra, Trypas Corassão – A Ópera

Cigarra

We are bodies at risk, so we have a political stamp. But instead of bringing this in an obvious way, we want to show our pulse of life. We want to shout that we are alive.

Tita Maravilha

We are alive according to the subjectivities of this political body, that is always political in relation to the world. But I’m also increasingly hitting this key that when people leave their homes, we’re talking about an extremely tired world. We’re all tired. On the theme of gender identity, we’re exhausted. You can quote me!

People have made themselves available to come and see us perform. So it’s a pact, right? It’s important to make people understand that they are alive too and to generate willingness to be moved together. This is a super political process, more than just our own presence. I am used to it, when I’m on the street, in the market… Here it’s different. This connection with other people is something that is important to be talked about. We will always hit the key of audience formation, so we have many people who come back to us. When there is a need, somehow, we are a way to escape. We fill a need in a certain place and it has to do with the strength of these two women: a cis woman, a trans woman, two non-white people, immigrants. We are the marginal beauty, and we want to somehow re-accustom the gaze. That’s why we talk about “beauty as revenge”. We can’t let the history of beauty, the history of opera, etc., stay with white, cis, thin, tech-savvy people, we must somehow redistribute that to the periphery.

10. The (female) body as manifest

Xana Novais, How to Kill Naked Women

I think art is a political manifestation, no doubt. I am a feminist, I consider myself a feminist. In How To Kill Naked Women, we speak out: “we are here, we have the privilege to be here, we are here to be able to massacre our bodies”. But there are women whose bodies are massacred without them wanting to. There are women in the past, who could not make decisions to mark, to inflict pain on themselves. In other words, we are inflicting pain, but we authorise it, because we want it.

It was very interesting to create this cycle at the end of almost us giving our bodies, giving our blood almost like a wafer, as an offering to those who were not able to do that. When I say on stage “using the body, we manifest”, that’s what I’m talking about: the power of decision.