Nudity as a trope in dance that leaves me ambivalent. Having grown up in the stereotypically prudish and reserved UK, I’ve long questioned whether shedding clothes is always necessary, or simply a cheap shock tactic. But after living in Germany for the duration of my twenties, where the body is more freely revealed both onstage and off, I’ve come to see the exposure of flesh as something that can carry a multitude of meanings.

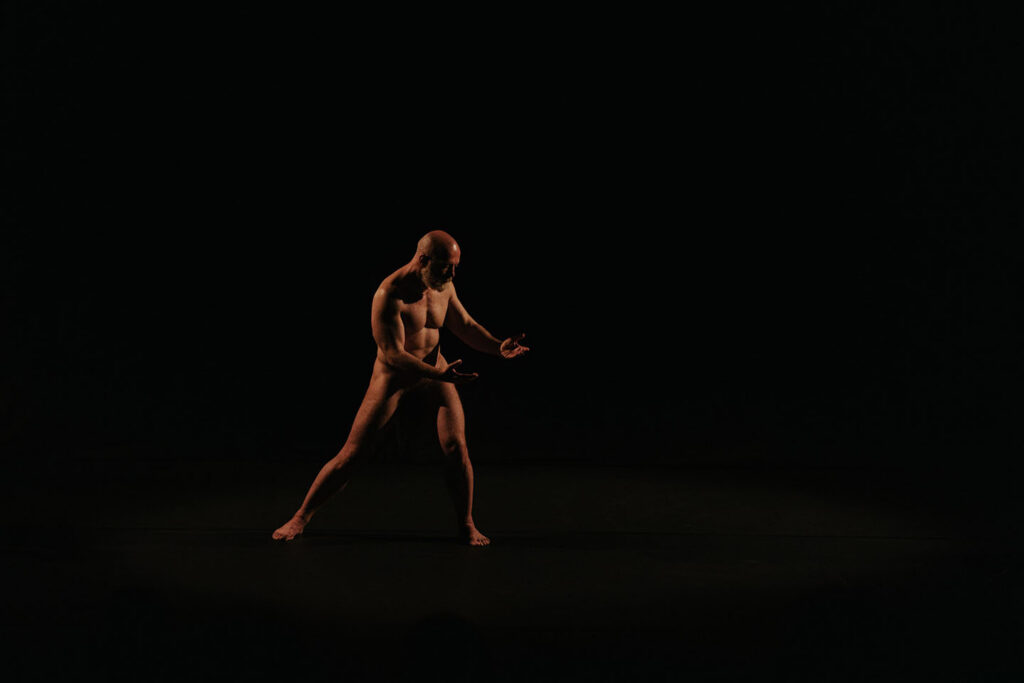

60% of the works in Moving Balkans came with the warning “contains nudity”. Yet, it was only DILF by Serbian choreographer Marco Milić that used it in an explicitly sexual way. Aiming to question whether all of our strongest erotic fantasies are in fact rooted in trauma, the solo sees Svetozar Adamović, a retired principal dancer of the Belgrade National Theatre, slowly morph between Greco-Roman-like sculptural poses. His face is stony and almost haunted as a voiceover – his inner monologue? – describes intimate desires ranging from “lick[ing] the ass of my girlfriend” to “threesomes.”

Many statements in the text contradict each other, with “I’ve never had a relationship with a man” being shortly followed by “I like a hard dick” and “big hairy men.” Others lines function purely as verbal self harm. “Look at you, you’re pathetic, useless as fuck,” the voice says at one point. I can’t say I haven’t had similarly self-critical thoughts when observing my own body in the mirror.

DILF’s use of explicit language, references to queer sexual experiences, and conclusive graphic masturbation scene, makes it a brave, provocative piece considering the context in which it was created. “There is still strong discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people [in Serbia],” Moving Balkans Serbian partner Marija (Zmaja) Popović tells me after the show. “[The country] is kind of split into two universes,” she adds: there are anti-discrimination laws, but same-sex marriage has not been adopted. Also, while many protest for greater diversity and acceptance, attitudes differ greatly between those in cities and the countryside.

For Popović, it is a shame that such discrimination persists given Serbia’s history of “avant-garde, advanced” views under socialist Yugoslavia. “Women got voting rights in 1941, there were movies in the 80s about transgender topics, and there was a very strong gay movement,” she says.

The fact that a naked body on stage can embody and reference complex human histories and emotions such as this is nothing short of astonishing. In contrast, in other works at Moving Balkans, bare skin served a more scientific than emotional purpose. The duet BLOT – Body Line Of Thought, by Romanian and Canadian choreographers Simona Deaconescu and Vanessa Goodman, explores the bacteria that live on and within the body. At one point, again by way of spoken text, it questions whether the performers are truly naked when their skin in fact crawls with billions of invisible organisms.

With robotic, emotionless voices, the pair describe how the lengths of their organs compare to world landmarks, and execute jerky, angular limb extensions as if presenting them to be measured. The mood is sterile and clinical, the dancers’ expressionless faces echoing Adamović’s in DILF, yet here, they suggest dehumanisation rather than trauma-induced repression.

I feel my own skin crawling when they start tracking and sharing their heart rates with each other – measured by sports watches as they skip repetitively with ropes. Having just got my own Garmin to track my exercise regime, I myself frequently share my excitement at my lowering average resting heart rate with my dad. Do I really want to become a body reduced to mere physical functions, like Deaconescu and Goodman are on stage? A mechanical vessel hosting bacteria rather than a thinking, feeling self? Or do thinking and feeling just lead to a traumatised relationship with my body, like Adamović in DILF?

Of course, these aren’t the only two options. Perhaps most aspirational is the way many of the performers at Moving Balkans, after having performed naked, step forward proudly for their bow without donning a robe for modesty, as I’m used to seeing elsewhere. Instead, they stand strong, confident, and comfortable in their own skin, allowing their body to receive the applause for the work it’s just done. We could all do with giving our bodies more credit.